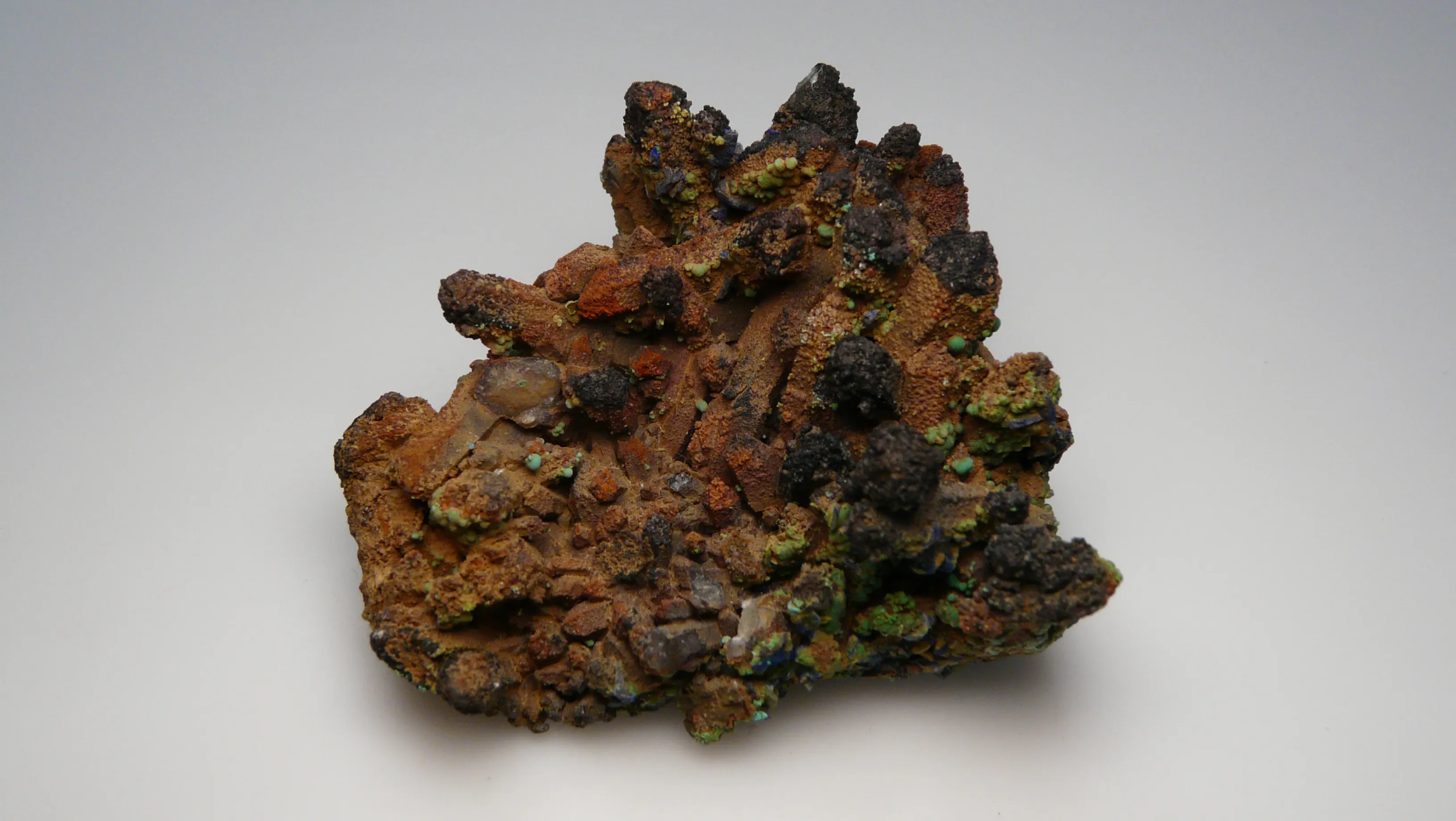

Quartz, Hematite, Goethite, Malachite and Azurite

| ID | 340 | |

|---|---|---|

| Mineral |

Quartz

Hematite Goethite Malachite Azurite |

|

| Location | Bou Azzer - Bou Azzer - Morocco | |

| Fluorescence | LW-UV: close SW-UV: close |

|

| Mindat.org |

View Quartz information at mindat.org View Hematite information at mindat.org View Goethite information at mindat.org View Malachite information at mindat.org View Azurite information at mindat.org |

|

Mindat data

| ID | 3337 |

|---|---|

| Long ID | 1:1:3337:0 |

| Formula |

SiO2

|

| IMA Status |

0 1 |

| Other Occurrences | Most of them... |

| Industrial | Ore for silicon, glassmaking, frequency standards, optical instruments, silica source for concrete setting, filtering agents as sand. A major component of sand. |

| Diapheny | Transparent,Translucent |

| Cleavage |

The rhombohedral cleavage r |

| Tenacity | brittle |

| Colour | Colorless, purple, rose, red, black, yellow, brown, green, blue, orange, etc. |

| Hardness (min) | 7.0 |

| Hardness (max) | 7.0 |

| Luminescence | Triboluminescent |

| Lustre | Vitreous |

| About the name | Quartz has been known and appreciated since pre-historic times. The most ancient name known is recorded by Theophrastus in about 300-325 BCE, κρύσταλλος or kristallos. The varietal names, rock crystal and bergcrystal, preserve the ancient usage. The root words κρύοσ signifying ice cold and στέλλειυ to contract (or solidify) suggest the ancient belief that kristallos was permanently solidified ice. The earliest printed use of "querz" was anonymously published in 1505, but attributed to a physician in Freiberg, Germany, Ulrich Rülein von Kalbe (a.k.a. Rülein von Calw, 1527). Agricola used the spelling "quarzum" (Agricola 1530) as well as "querze", but Agricola also referred to "crystallum", "silicum", "silex", and silice". Tomkeieff (1941) suggested an etymology for quartz: "The Saxon miners called large veins - Gänge, and the small cross veins or stringers - Querklüfte. The name ore (Erz, Ertz) was applied to the metallic minerals, the gangue or to the vein material as a whole. In the Erzgebirge, silver ore is frequently found in small cross veins composed of silica. It may be that this ore was called by the Saxon miners 'Querkluftertz' or the cross-vein-ore. Such a clumsy word as 'Querkluftertz' could easily be condensed to 'Querertz' and then to 'Quertz', and eventually become 'Quarz' in German, 'quarzum' in Latin and 'quartz' in English." Tomkeieff (1941, q.v.) noted that "quarz", in its various spellings, was not used by other noted contemporary authors. "Quarz" was used in later literature referring to the Saxony mining district, but seldom elsewhere. Gradually, there were more references to quartz: E. Brown in 1685 and Johan Gottschalk Wallerius in 1747. In 1669, Nicolaus Steno (Niels Steensen) obliquely formulated the concept of the constancy of interfacial angles in the caption of an illustration of quartz crystals. He referred to them as "cristallus" and "crystallus montium". Tomkeieff (1941) also noted that Erasmus Bartholinus (1669) used the various spellings for "crystal" to signify other species than quartz and that crystal could refer to other "angulata corpora" (bodies with angles): "In any case in the second half of the XVIIIth century quartz became established as a name of a particular mineral and the name crystal became a generic term synonymous with the old term 'corpus angulatum'." |

| Streak | White |

| Crystal System | Trigonal |

| Cleavage Type | Poor/Indistinct |

| Fracture type | Conchoidal |

| Twinning | Dauphiné law. Brazil law. Japan law. Others for beta-quartz... |

| Thermal Behaviour | Transforms to beta-quartz at 573° C and 1 bar (100 kPa) pressure. |

| shortcode_ima | Qz |

| ID | 1856 |

|---|---|

| Long ID | 1:1:1856:8 |

| Formula |

Fe2O3

|

| IMA Status |

0 1 |

| Other Occurrences | Large ore bodies of hematite are usually of sedimentary origin; also found in high-grade ore bodies in metamorphic rocks due to contact metasomatism, and occasionally as a sublimate on igneous extrusive rocks ("lavas") as a result of volcanic activity. It is also usually the cause of red soils all over the planet. |

| Industrial | A major ore of iron. |

| Diapheny | Opaque |

| Tenacity | brittle |

| Colour | Steel-grey to black in crystals and massively crystalline ores, dull to bright "rust-red" in earthy, compact, fine-grained material. |

| Hardness (min) | 5.0 |

| Hardness (max) | 6.0 |

| Luminescence | None |

| Lustre | Metallic |

| About the name | Originally named about 300-325 BCE by Theophrastus from the Greek, "αιματίτις λίθος" ("aematitis lithos") for "blood stone". It is possibly the first mineral ever named ending with a "-ite" suffix. Translated in 79 by Pliny the Elder to haematites, "bloodlike", in allusion to the vivid red colour of the powder. The modern form evolved by authors frequently simplifying the spelling by excluding the "a", somewhat in parallel with other words originally utilising the root "haeme". |

| Streak | Reddish brown ("rust-red") |

| Crystal System | Trigonal |

| Cleavage Type | None Observed |

| Fracture type | Irregular/Uneven,Sub-Conchoidal |

| Morphology |

|

| Twinning |

|

| UV | None. |

| shortcode_ima | Hem |

| Group | Hematite Group |

| ID | 1719 |

|---|---|

| Long ID | 1:1:1719:6 |

| Formula |

FeO(OH)

|

| IMA Status |

0 1 |

| Other Occurrences | Common weathering product, primary hydrothermal mineral, bog and marine environments. |

| Industrial | Iron ore |

| Discovery Year | 1806 |

| Diapheny | Opaque |

| Cleavage | {010}; {100} less perfect. |

| Tenacity | brittle |

| Colour | Brownish black, yellow-brown, reddish brown |

| Hardness (min) | 5.0 |

| Hardness (max) | 5.5 |

| About the name | Named in 1806 by Johann Georg Lenz in honor of the German poet, novelist, playwrighter, philosopher, politician, and geoscientist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe [August 28, 1749, Frankfurt, Germany – March 22, 1832, Weimar, Germany]. Goethe was Chief Minister of State of Weimar. (Portions of the Goethe mineral collection are reputedly held by the Goethe Society in New York, New York, USA.) |

| Streak | Yellowish brown, orange-yellow, ocher-yellow |

| Crystal System | Orthorhombic |

| Cleavage Type | Perfect |

| Fracture type | Irregular/Uneven |

| Morphology | Prismatic [001] and striated [001]; also flattened into tablets or scales on {010}. Velvety aggregates of capillary crystals to acicular [001] and long prismatic forms often radially grouped. Massive, reniform, botryoidal, stalactitic. Bladed or columnar. Compact or fibrous concretionary nodules. Oolitic. |

| Twinning |

Apparently none reported, but see https://www.mindat.org/mesg-631125.html and compare twinning in isostructural |

| Thermal Behaviour | Heated in a closed tube, gives off water. |

| shortcode_ima | Gth |

| Group | Diaspore Group |

| ID | 2550 |

|---|---|

| Long ID | 1:1:2550:4 |

| Formula |

Cu2(CO3)(OH)2

|

| IMA Status |

0 1 |

| Other Occurrences | It is the most common secondary mineral found in the oxidized zones of copper deposits. |

| Industrial | A minor ore of copper when abundant enough in a copper deposit. |

| Discovery Year | Unno |

| Diapheny | Opaque |

| Cleavage |

Perfect on |

| Tenacity | brittle |

| Colour | Bright green, with crystals deeper shades of green, even very dark to nearly black; green to yellowish green in transmitted light. |

| Hardness (min) | 3.5 |

| Hardness (max) | 4.0 |

| About the name | Named in antiquity (see Pliny the Elder, 79 CE) molochitus after the Greek μαλαχή, "mallows," in allusion to the green color of the leaves. Known in the new spelling, malachites, at least by 1661. |

| Streak | Light green |

| Crystal System | Monoclinic |

| Cleavage Type | Perfect |

| Fracture type | Splintery |

| Morphology | Crystals uncommon, usually short or long prismatic or acicular, parallel to [001]; often grouped in rosettes, sprays, or tufts. Botryoidal to mammillary aggregates of radiating fibrous crystals more common. It may also be massive, compact, and stalactitic. |

| Twinning | Untwinned crystals are extremely rare. Typically twinned on {100}, sometimes as penetration or polysynthetic twinning with the axis parallel to [201]. |

| Thermal Behaviour | Loses water at about 315°, leaving tenorite. |

| key_elements |

0 |

| shortcode_ima | Mlc |

| Group | Rosasite Group |

| ID | 447 |

|---|---|

| Long ID | 1:1:447:3 |

| Formula |

Cu3(CO3)2(OH)2

|

| IMA Status |

0 1 |

| Other Occurrences | Found largely in the oxidized portions of copper deposits, it is a secondary mineral formed by the action of carbonated water acting on copper-containing minerals, or from Cu-containing solutions, such as CuSO^4 or CuCl^2 reacting with limestones. |

| Industrial | A very minor ore of copper. |

| Discovery Year | 1824 |

| Diapheny | Transparent,Translucent |

| Cleavage | Perfect on {011}; on {100} fair; on {110} in traces. |

| Tenacity | brittle |

| Colour | Azure blue, blue, light blue, or dark blue; light blue in transmitted light |

| Hardness (min) | 3.5 |

| Hardness (max) | 4.0 |

| Luminescence | None |

| Lustre | Vitreous |

| About the name | From the ancient Persian lazhward, meaning "blue", in allusion to the color. Name changed to azurite in 1824 by François Sulpice Beudant. |

| Streak | Light blue |

| Crystal System | Monoclinic |

| Cleavage Type | Perfect |

| Fracture type | Conchoidal |

| Morphology |

Tabular {001}, less common {102} or |

| Twinning |

Rare, across |

| UV | None. |

| key_elements |

0 |

| shortcode_ima | Azu |

Details

Price: € 20

Dimensions: Not registered

Weight: 96 g

Visibile in overview:

Notes:

| Symbol | Element | |

|---|---|---|

| C | Carbon | |

| Cu | Copper | |

| Fe | Iron | |

| H | Hydrogen | |

| O | Oxygen | |

| Si | Silicium |